eros et thanatos

2683k

1999.01.29

abstract done

1999.02.23 19:08

"Inside the Density of G. B. Piranesi's Ichnographia Campi Martii"

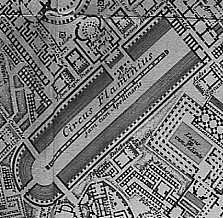

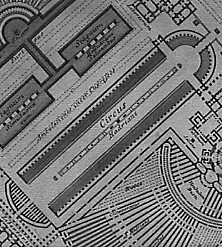

Albeit resolutely virtual, Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius nonetheless manifests a high degree of density not only in terms of architecture and urbanism, but with regard to symbolism, meaning, and narrative as well. The hundreds of individual building plans and their Latin labels within the Campo Marzio do not "reconstruct" ancient Rome as much as they "reenact" it. Thus Piranesi's overall large plan presents a design of Rome that reflects and narrates Rome's own imperial history. Given Rome's history then, the ultimate theme of Piranesi's design is inversion, specifically ancient Rome's inversion from (dense) pagan capital of the world to (dense) Christian capital of the world--a prime example of the proverbial "two sides to every story."

With the inversion theme, Piranesi also incorporates a number of sub-themes, such as life and death, love and war, satire, and even urban sprawl. Rendered largely independent, each sub-theme relates its own "story." Due to their innate reversal qualities, however, each sub-theme also reinforces the main inversion theme. Piranesi's Campo Marzio is not only dense, it is condensed.

In 2001, the finished Ichnographia Campus Martius will be 240 years old, yet Piranesi's truly unique urban paradigm--a city "reenacting" itself through all its physical, socio-political, and even metaphysical layers--may well become the most real urban paradigm of the next millennium.

21 April 1999 (Rome's birthday)

1999.04.21

The path that ultimately lead me to Helena began with my learning about a deliberate connection between Piranesi's Ichnographia Campus Martius and Saint Agnes of Rome. According to ancient tradition, the first "structure" within the Campus Martius was an altar erected by Romulus in honor of his father Mars. Piranesi situates the Ara Martis within the generally accepted location of the original altar, that is, within the area between the present day Piazza Navona and the Tiber to the west. In Piranesi's plan, the altar of Mars is within a circular pool in front of a Temple of Mars and is furthermore surrounded by an extensively curvilinear porticus. Additionally, the Domus Alexandri Severus (1) flanked by two Sessorium (2) is to the west.

Investigating the meaning of Piranesi's Ara Martis layout, I looked to Nolli's 1748 Plan of Rome for a possible connection. I chose this approach because I had already learned that Piranesi indeed sometimes cleverly disguised links between his Ichnographia and Nolli's plan. The only potential tie between the two maps at the Ara Martis juncture is the coinciding position of the Templum Martis and the baroque church of St. Agnes on the Piazza Navona. At this point it became necessary for me to investigate the story of Saint Agnes.

Saint Agnes died in Rome circa 249 as a thirteen year old virgin and martyr. "Her riches and beauty excited the young noblemen of the first families of Rome to contend as rivals for her hand. Agnes answered them all that she had consecrated her virginity to a heavenly husband, who could not be beheld by mortal eyes. Her suitors, finding her resolution unshakable, accused her to the governor as a Christian, not doubting that threats and torments would prove more effective with one of her tender years on whom allurements could make no impression."1 As a form of torture, Agnes was sent to a brothel where her vow of virginity would be threatened and almost certainly eradicated. According to the legend, however, an angel protected Agnes while she was in the brothel, and subsequently Agnes was put to death. The traditional location of the brothel of Agnes' torture is the site of St. Agnes on the Piazza Navona. Moreover, the subsequent execution of Agnes sent shockwaves throughout both pagan and Christian Rome because the worst possible thing any Roman could do was to kill a virgin. Suddenly, and ironically, the Roman persecution of Christians took on the guise of a pagan moral dilemma.

The martyrdom of Agnes signifies a pivotal point of pagan-Christian inversion, and this inversion is precisely what Piranesi delineates within the complex of the Ara Martis. First, the co-positioning of the Templum Martis and the church of St. Agnes represents the origin of Rome itself when Mars raped the Vestal Virgin Rhea, who subsequently became mother to Romulus and Remus. Second, the emperor Alexander Severus is known for having been very interested and sympathetic towards Christianity, to the point where he seriously considered proclaiming Jesus as one of the official Roman gods as well as carving the (inverting) words "do unto others as you would have them do unto you" over the door of his house. Third, Sessorium is a direct reference to the Palatium Sessorianum, the imperial estate that became Helena's residence in Rome after 312, and soon thereafter the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme. It seems quite evident that Piranesi was well aware of early Christian history, including its architectural history.

Personally, I wonder whether Piranesi recognized Helena as an architect as well.

1 Herbert Thurston, S.J. and Donald Attwater, editors, "St Agnes" in Butler's Lives of the Saints (New York: P.J. Kenedy & Sons, 1956), v. 1, pp. 133-4.

| |

engraving and inversion (reversal) - Piranesi

1999.06.14

Pagan - Christian - Triumphal Way

3123h

3123i

3123j

3123k

1999.11.21

Really Good Architecture

2001.01.15

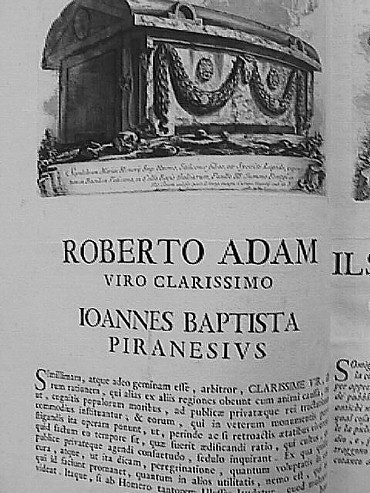

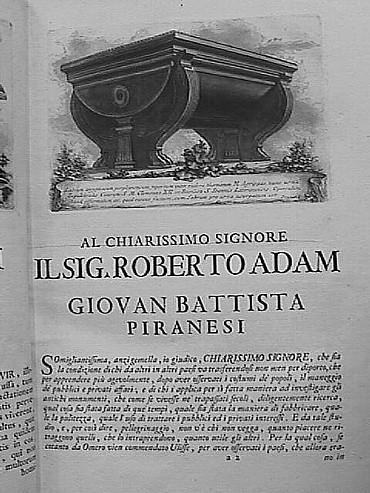

...this morning the postman delivered a Piranesi print, a print which I successfully bid on last weekend at eBay. It was the architecture of eBay that brought me Piranesi's engraving of ancient Rome's last Imperial artifact. I was confident in bidding on the print online via a written description and two digital images because of the Piranesi research that I have done and continue to do at home, online, and at university libraries. [By the way, Piranesi is a great proto-virtual-place architect.] This print of the sarcophagus of Maria, wife of the Emperor Honorius, was originally published within Piranesi's Il Campo Marzio (1762), specifically at the head of the dedicatory letter to Robert Adam. In true inversionary fashion, Piranesi cleverly placed an image of ancient Rome's last Imperial artifact at the beginning of the Il Campo Marzio publication.

|